By Jacob Wang

Introduction

A diverse and comprehensive set of libraries is important to any productive software ecosystem. While it is easy to develop and distribute Scala libraries, good library authorship goes beyond just writing code and publishing it.

In this guide, we will cover the important topic of Binary Compatibility:

- How binary incompatibility can cause production failures in your applications

- How to avoid breaking binary compatibility

- How to reason about and communicate the impact of their code changes

Before we start, let’s understand how code is compiled and executed on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM).

The JVM execution model

Scala is compiled to a platform-independent format called JVM bytecode and stored in .class files.

These class files are collated in JAR files for distribution.

When some code depends on a library, its compiled bytecode references the library’s bytecode. The library’s bytecode is referenced by its class/method signatures and loaded lazily by the JVM classloader during runtime. If a class or method matching the signature is not found, an exception is thrown.

As a result of this execution model:

- We need to provide the JARs of every library used in our dependency tree when starting an application since the library’s bytecode is only referenced, not merged into its user’s bytecode

- A missing class/method problem may only surface after the application has been running for a while, due to lazy loading.

Common exceptions from classloading failures includes

InvocationTargetException, ClassNotFoundException, MethodNotFoundException, and AbstractMethodError.

Let’s illustrate this with an example:

Consider an application App that depends on A which itself depends on library C. When starting the application we need to provide the class files

for all of App, A and C (something like java -cp App.jar:A.jar:C.jar:. MainClass). If we did not provide C.jar or if we provided a C.jar that does not contain some classes/methods

which A calls, we will get classloading exceptions when our code attempts to invoke the missing classes/methods.

These are what we call Linkage Errors – errors that happen when the compiled bytecode references a name that cannot be resolved during runtime.

What about Scala.js and Scala Native?

Similarly to the JVM, Scala.js and Scala Native have their respective equivalents of .class files, namely .sjsir files and .nir files. Similarly to .class files, they are distributed in .jars and linked together at the end.

However, contrary to the JVM, Scala.js and Scala Native link their respective IR files at link time, so eagerly, instead of lazily at run-time. Failure to correctly link the entire program results in linking errors reported while trying to invoke fastOptJS/fullOptJS or nativeLink.

Besides, that difference in the timing of linkage errors, the models are extremely similar. Unless otherwise noted, the contents of this guide apply equally to the JVM, Scala.js and Scala Native.

Before we look at how to avoid binary incompatibility errors, let us first establish some key terminologies we will be using for the rest of the guide.

What are Evictions, Source Compatibility and Binary Compatibility?

Evictions

When a class is needed during execution, the JVM classloader loads the first matching class file from the classpath (any other matching class files are ignored). Because of this, having multiple versions of the same library in the classpath is generally undesirable:

- Need to fetch and bundle multiple library versions when only one is actually used

- Unexpected runtime behavior if the order of class files changes

Therefore, build tools like sbt and Gradle will pick one version and evict the rest when resolving JARs to use for compilation and packaging. By default, they pick the latest version of each library, but it is possible to specify another version if required.

Source Compatibility

Two library versions are Source Compatible with each other if switching one for the other does not incur any compile errors or unintended behavioral changes (semantic errors).

For example, If we can upgrade v1.0.0 of a dependency to v1.1.0 and recompile our code without any compilation errors or semantic errors, v1.1.0 is source compatible with v1.0.0.

Binary Compatibility

Two library versions are Binary Compatible with each other if the compiled bytecode of these versions can be interchanged without causing Linkage Errors.

Relationship between source and binary compatibility

While breaking source compatibility often results in binary incompatibilities as well, they are actually orthogonal – breaking one does not imply breaking the other.

Forward and Backward Compatibility

There are two “directions” when we describe compatibility of a library release:

Backward Compatible means that a newer library version can be used in an environment where an older version is expected. When talking about binary and source compatibility, this is the common and implied direction.

Forward Compatible means that an older library can be used in an environment where a newer version is expected. Forward compatibility is generally not upheld for libraries.

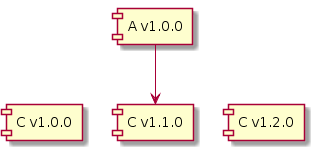

Let’s look at an example where library A v1.0.0 is compiled with library C v1.1.0.

C v1.1.0 is Forwards Binary Compatible with v1.0.0 if we can use v1.0.0’s JAR at runtime instead of v1.1.0’s JAR without any linkage errors.

C v1.2.0 is Backward Binary Compatible with v1.1.0 if we can use v1.2.0’s JAR at runtime instead of v1.1.0’s JAR without any linkage errors.

Why binary compatibility matters

Binary Compatibility matters because breaking binary compatibility has bad consequences on the ecosystem around the software.

- End users have to update versions transitively in all their dependency tree such that they are binary compatible. This process is time-consuming and error-prone, and it can change the semantics of end program.

- Library authors need to update their library dependencies to avoid “falling behind” and causing dependency hell for their users. Frequent binary breakages increase the effort required to maintain libraries.

Constant binary compatibility breakages in libraries, especially ones that are used by other libraries, is detrimental to our ecosystem as they require time and effort from end users and maintainers of dependent libraries to resolve.

Let’s look at an example where binary incompatibility can cause grief and frustration:

An example of “Dependency Hell”

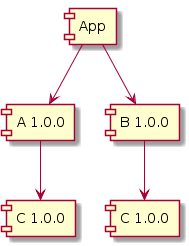

Our application App depends on library A and B. Both A and B depends on library C. Initially, both A and B depends on C v1.0.0.

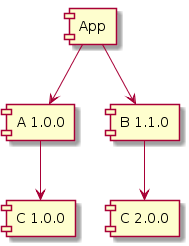

Sometime later, we see B v1.1.0 is available and upgrade its version in our build. Our code compiles and seems to work, so we push it to production and go home for dinner.

Unfortunately at 2am, we get frantic calls from customers saying that our application is broken! Looking at the logs, you find lots of NoSuchMethodError are being thrown by some code in A!

Why did we get a NoSuchMethodError? Remember that A v1.0.0 is compiled with C v1.0.0 and thus calls methods available in C v1.0.0.

While B v1.1.0 and App has been recompiled with C v2.0.0, A v1.0.0’s bytecode hasn’t changed - it still calls the method that is now missing in C v2.0.0!

This situation can only be resolved by ensuring that the chosen version of C is binary compatible with all other evicted versions of C in your dependency tree. In this case, we need a new version of A that depends

on C v2.0.0 (or any other future C version that is binary compatible with C v2.0.0).

Now imagine if App is more complex with lots of dependencies themselves depending on C (either directly or transitively) - it becomes extremely difficult to upgrade any dependencies because it now

pulls in a version of C that is incompatible with the rest of C versions in our dependency tree!

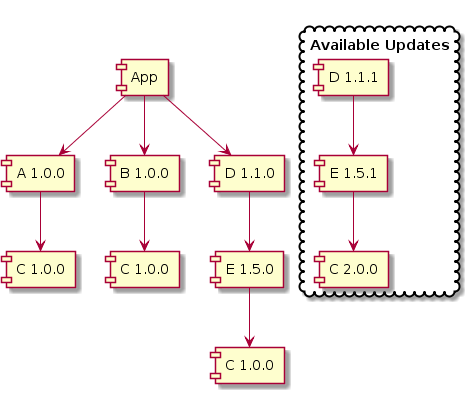

In the example below, we cannot upgrade to D v1.1.1 because it will transitively pull in C v2.0.0, causing breakages

due to binary incompatibility. This inability to upgrade any packages without breaking anything is commonly known as Dependency Hell.

How can we, as library authors, spare our users of runtime errors and dependency hell?

- Use Migration Manager (MiMa) to catch unintended binary compatibility breakages before releasing a new library version

- Avoid breaking binary compatibility through careful design and evolution of your library interfaces

- Communicate binary compatibility breakages clearly through versioning

MiMa - Checking binary compatibility against previous library versions

MiMa is a tool for diagnosing binary incompatibilities between different library versions.

It works by comparing the class files of two provided JARs and report any binary incompatibilities found.

Both backwards and forwards binary incompatibility can be detected by swapping input order of the JARs.

By incorporating MiMa’s sbt plugin into your sbt build, you can easily check whether you have accidentally introduced binary incompatible changes. Detailed instruction on how to use the sbt plugin can be found in the link.

We strongly encourage every library author to incorporate MiMa into their continuous integration and release workflow.

Detecting backwards source compatibility is difficult with Scala due to language features like implicit and named parameters. The best approximation to checking backwards source compatibility is running both forwards and backwards binary compatibility check, as this can detect most cases of source-incompatible changes. For example, adding/removing public class members is a source incompatible change, and will be caught through forward + backward binary compatibility check.

Evolving code without breaking binary compatibility

Binary compatibility breakages can often be avoided through the careful use of certain Scala features as well as some techniques you can apply when modifying code.

For example, the use of these language features are a common source of binary compatibility breakages in library releases:

- Default parameter values for methods or classes

- Case classes

You can find detailed explanations, runnable examples and tips to maintain binary compatibility in Binary Compatibility Code Examples & Explanation.

Again, we recommend using MiMa to double-check that you have not broken binary compatibility after making changes.

Changing a case class definition in a backwards-compatible manner

Sometimes, it is desirable to change the definition of a case class (adding and/or removing fields) while still staying backwards-compatible with the existing usage of the case class, i.e. not breaking the so-called binary compatibility. The first question you should ask yourself is “do you need a case class?” (as opposed to a regular class, which can be easier to evolve in a binary compatible way). A good reason for using a case class is when you need a structural implementation of equals and hashCode.

To achieve that, follow this pattern:

- make the primary constructor private (this makes the

copymethod of the class private as well) - define a private

unapplyfunction in the companion object (note that by doing that the case class loses the ability to be used as an extractor in match expressions) - for all the fields, define

withXXXmethods on the case class that create a new instance with the respective field changed (you can use the privatecopymethod to implement them) - create a public constructor by defining an

applymethod in the companion object (it can use the private constructor) - in Scala 2, you have to add the compiler option

-Xsource:3

Example:

// Mark the primary constructor as private

case class Person private (name: String, age: Int) {

// Create withXxx methods for every field, implemented by using the (private) copy method

def withName(name: String): Person = copy(name = name)

def withAge(age: Int): Person = copy(age = age)

}

object Person {

// Create a public constructor (which uses the private primary constructor)

def apply(name: String, age: Int) = new Person(name, age)

// Make the extractor private

private def unapply(p: Person): Some[Person] = Some(p)

}

// Mark the primary constructor as private

case class Person private (name: String, age: Int):

// Create withXxx methods for every field, implemented by using the (private) copy method

def withName(name: String): Person = copy(name = name)

def withAge(age: Int): Person = copy(age = age)

object Person:

// Create a public constructor (which uses the private primary constructor)

def apply(name: String, age: Int): Person = new Person(name, age)

// Make the extractor private

private def unapply(p: Person) = p

This class can be published in a library and used as follows:

// Create a new instance

val alice = Person("Alice", 42)

// Transform an instance

println(alice.withAge(alice.age + 1)) // Person(Alice, 43)

If you try to use Person as an extractor in a match expression, it will fail with a message like “method unapply cannot be accessed as a member of Person.type”. Instead, you can use it as a typed pattern:

alice match {

case person: Person => person.name

}

alice match

case person: Person => person.name

Later in time, you can amend the original case class definition to, say, add an optional address field. You

- add a new field

addressand a customwithAddressmethod, - update the public

applymethod in the companion object to initialize all the fields,

case class Person private (name: String, age: Int, address: Option[String]) {

...

def withAddress(address: Option[String]) = copy(address = address)

}

object Person {

// Update the public constructor to also initialize the address field

def apply(name: String, age: Int): Person = new Person(name, age, None)

}

case class Person private (name: String, age: Int, address: Option[String]):

...

def withAddress(address: Option[String]) = copy(address = address)

object Person:

// Update the public constructor to also initialize the address field

def apply(name: String, age: Int): Person = new Person(name, age, None)

The original users can use the case class Person as before, all the methods that existed before are present unmodified after this change, thus the compatibility with the existing usage is maintained.

The new field address can be used as follows:

// The public constructor sets the address to None by default.

// To set the address, we call withAddress:

val bob = Person("Bob", 21).withAddress(Some("Atlantic ocean"))

println(bob.address)

A regular case class not following this pattern would break its usage, because by adding a new field changes some methods (which could be used by somebody else), for example copy or the constructor itself.

Optionally, you can also add overloads of the apply method in the companion object to initialize more fields

in one call. In our example, we can add an overload that also initializes the address field:

object Person {

// Original public constructor

def apply(name: String, age: Int): Person = new Person(name, age, None)

// Additional constructor that also sets the address

def apply(name: String, age: Int, address: String): Person =

new Person(name, age, Some(address))

}

object Person:

// Original public constructor

def apply(name: String, age: Int): Person = new Person(name, age, None)

// Additional constructor that also sets the address

def apply(name: String, age: Int, address: String): Person =

new Person(name, age, Some(address))

Versioning Scheme - Communicating compatibility breakages

Library authors use versioning schemes to communicate compatibility guarantees between library releases to their users. Versioning schemes like Semantic Versioning (SemVer) allow users to easily reason about the impact of updating a library, without needing to read the detailed release notes.

In the following section, we will outline a versioning scheme based on Semantic Versioning that we strongly encourage you to adopt for your libraries. The rules listed below are in addition to Semantic Versioning v2.0.0.

Recommended Versioning Scheme

Given a version number MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, you MUST increment the:

- MAJOR version if backward binary compatibility is broken,

- MINOR version if backward source compatibility is broken, and

- PATCH version to signal neither binary nor source incompatibility.

According to SemVer, patch versions should contain only bug fixes that fix incorrect behavior so major behavioral change in method/classes should result in a minor version bump.

- When the major version is

0, a minor version bump may contain both source and binary breakages.

Some examples:

v1.0.0 -> v2.0.0is binary incompatible. End users and library maintainers need to update all their dependency graph to remove all dependency onv1.0.0.v1.0.0 -> v1.1.0is binary compatible. Classpath can safely contain bothv1.0.0andv1.1.0. End user may need to fix minor source breaking changes introducedv1.0.0 -> v1.0.1is source and binary compatible. This is a safe upgrade that does not introduce binary or source incompatibilities.v0.4.0 -> v0.5.0is binary incompatible. End users and library maintainers need to update all their dependency graph to remove all dependency onv0.4.0.v0.4.0 -> v0.4.1is binary compatible. Classpath can safely contain bothv0.4.0andv0.4.1. End user may need to fix minor source breaking changes introduced

Many libraries in the Scala ecosystem has adopted this versioning scheme. A few examples are Akka, Cats and Scala.js.

Conclusion

Why is binary compatibility so important such that we recommend using the major version number to track it?

From our example above, we have learned two important lessons:

- Binary incompatibility releases often lead to dependency hell, rendering your users unable to update any of their libraries without breaking their application.

- If a new library version is binary compatible but source incompatible, the user can fix the compile errors and their application should work.

Therefore, binary incompatible releases should be avoided if possible and unambiguously documented when they happen, warranting the use of the major version number. Users of your library can then enjoy simple version upgrades and have clear warnings when they need to align library versions in their dependency tree due to a binary incompatible release.

If we follow all recommendations laid out in this guide, we as a community can spend less time untangling dependency hell and more time building cool things!